Thinais are world-making systems from the Sangam era, built on the idea that human feeling is inseparable from the environment. Literary critic S. Murali calls this “the earliest attempt at formulating an environmental aesthetic, where the human bhava (emotion) seeks its correspondence in the natural vibhava (cause).” Each thinai is named after local flora and is representative of the actual terrains of peninsular India, rooting its emotional worlds in the plants and ecologies that defined those regions. According to the ancient Tamil treatise Tholkappiyam, poetic expression falls into two broad modes: Akam and Puram. Akam turns inward. It is intimate, feminine, anonymous and centred on love in its many stages. Women shape much of its voice and temperament. Puram looks outward. It engages the masculine sphere, speaking of heroism, conflict, and public life. Its tone is largely shaped by men. Thinais are embedded within both Akam and Puram.

In the five Akam thinais, feelings unfold across landscape, time of day, colour, flora, and fauna, guided by a highly structured system of symbolism and metaphor that forms a complete cosmos. This sensorial logic finds strong resonance in the artistic traditions of the South, where narrative storytelling, masterful use of colour, and portraiture remain central. The exhibition reads this aesthetic lineage through the thinais, offering a unique context to the region’s distinct visual languages. While Sangam poets grounded their verse in the terrains and living worlds of each thinai, they also allowed elements to travel between regions, recognising that nature resisted strict boundaries. Within this framework, nearly any artwork from the subcontinent could be seen through the lens of its ecological and emotional bearings.

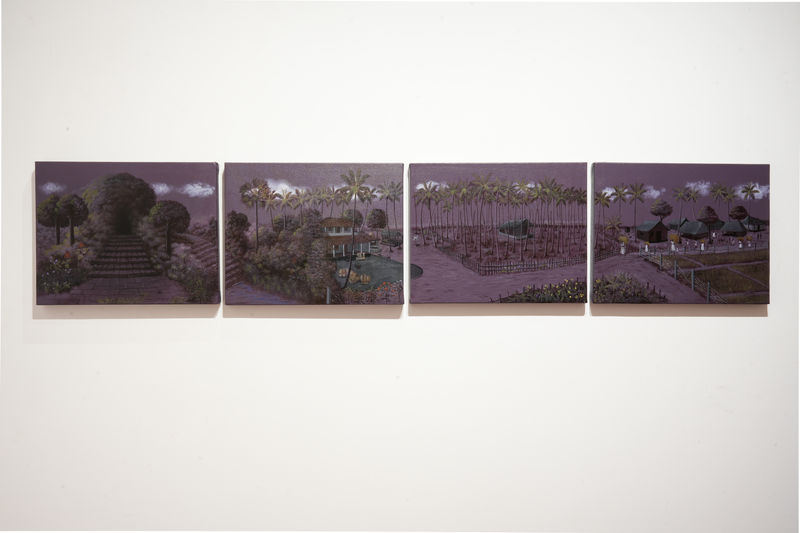

The artists gathered here each hold an intuitive link to these world-making systems. Kamala Das’ fierce, feminine Akam presence sits beside Riyas Komu’s Puram-driven works that confront war and our growing numbness to its consequences. Santhi E.N. 's command of purple, and her longing for childhood, aligns closely with the Kurinci thinai. Benitha Perciyal’s use of Tacoma seeds, Smitha G.S’s shola forests, and C.N. Karunakaran’s impressionist wetlands evoke the reciprocity between people and land at the heart of the Marutham thinai. Arieno Kera’s rhododendrons, rooted in the flora of her homeland, extend thinai-like sensibilities into another cultural landscape. K.G. Babu’s wide-eyed portraits, where figures remain inseparable from forested surroundings, recall the longing and intimacy of the Mullai thinai.

And Senaka Senanayake’s works on paper, distinct from his lush rainforest

canvases, take on the contemplative openness of the Neythal thinai. As the

exhibition took shape, we were often struck by how naturally the thinais

surfaced within these works. Human experience and the natural world are bound together, and as long as artists draw from this relationship, thinais endure. We invite you to take in the material, wander through these shifting landscapes of feeling, and have your own personal encounters with the artworks and the thinais they inhabit.